The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) passed in 2022 will soon be fully enacted. A major policy component included in the legislation is the implementation of Maximum Fair Price (MFP) negotiations for branded pharmaceutical products. For the first time, the federal government, under the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), has been empowered to centrally set drug prices for selected products.

The effects on the life sciences industry and ultimately to patient treatment are profound

MFP negotiations shorten a product’s economic lifecycle by introducing a new Medicare event horizon at nine years for small molecule drugs and 13 years for large molecule drugs. Effectively, MFP negotiations will act as a new Loss of Exclusivity date in the Medicare channel and operate independently of patent life. As such, the impact of a shortened lifecycle value can be immense, as it comes late when a brand is typically at its peak value. Additionally, there is little to suggest that new Medicare pricing will not be carried over to the employer-based insurance markets once MFP prices become public, extending a new floor to net prices.

The IRA is not happening in isolation

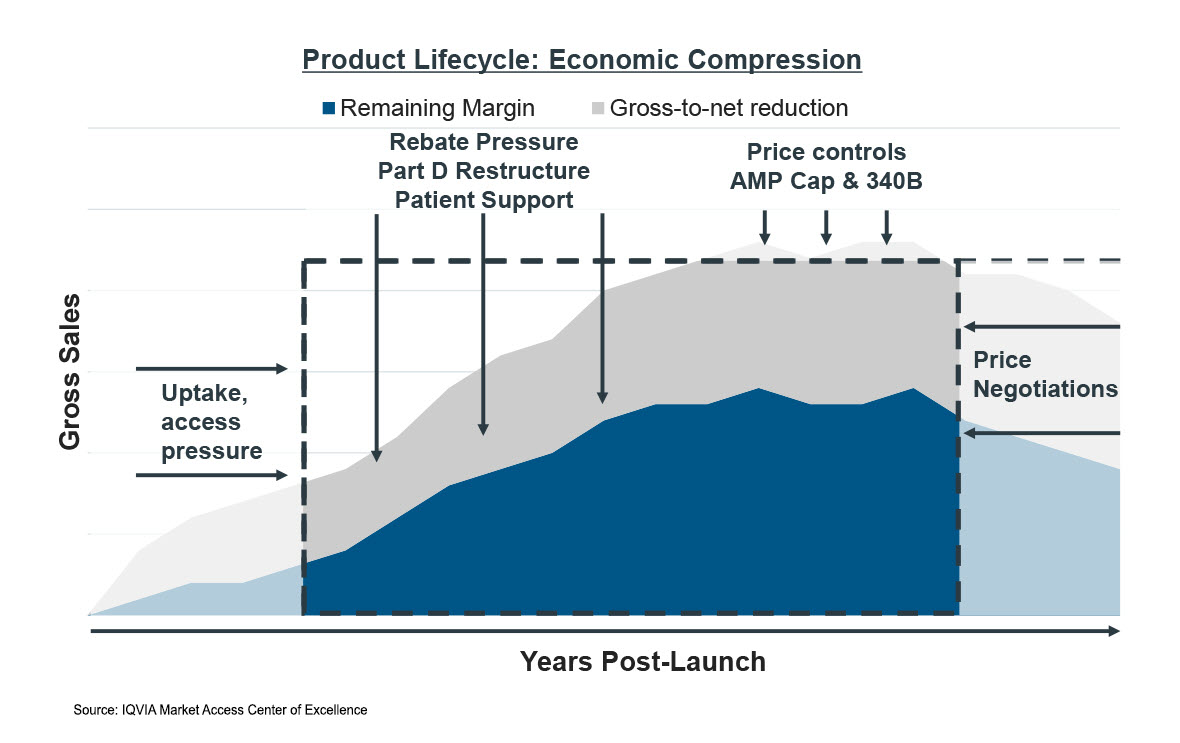

Other life sciences market dynamics are also influencing the economic life of a product [Figure 1].

- Recent pharmaceutical launch performance lags historical uptake as pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) market consolidation and vertical integration strategies increase the power of formulary controls. Slower uptake in the first few years of launch directly alter lifecycle economics and peak sales.

- Margin compression continues to accelerate as rebates, new IRA liabilities, patient copay offset costs, and 340B discounts grow. Drug pricing strategies are also altered as Medicaid best price policies remove the penny pricing cap (AMP Cap) and price inflation controls extend across all payer channels. Lower margins and lifecycle value directly impact funding available for research and development.

Combined, the net effect of these market dynamics is the compression of the economic lifecycle of a brand, both in terms of timeline and expected revenues. The effects will impact small molecule brands more intensely than large molecule brands due to the shorter timeline afforded these products under the law. However, the cumulative effects will be felt by the entire industry and will be carried over to treatments available to patients.

Knowing that the economic window is shrinking creates several emerging industry practices that will reshape investment into research and development of future products.

The fastest path to the market may no longer be the best economic path

Consider an FDA-designated orphan drug engaged in clinical trials that is given fast track status to an accelerated approval and has the potential for additional future indications. By granting fast track status, a high-need patient population will potentially gain access to much needed treatment. This is not an isolated case example. In 2022, 65% of approved novel drugs moved through an accelerated pathway— which meant they were meeting a substantial unmet need for serious life-threatening diseases.1

Under the IRA, getting that first indication starts the MFP clock ticking. Manufacturers must now consider the comparative value of the various potential indications to maximize the economic return of the product over its lifecycle. For multi-indication drugs, launching into a high need, but potentially smaller, indication first lessens the lifetime value of the product.

Should the manufacturer focus on the larger population first? What if that indication is more complex and does not have the same probability of success? What if there is a high-need patient population where there are no other available treatments? There are many ethical considerations in addition to economic ones.

Indication stacking versus indication sequencing to bring value forward

For the last two decades, the predominant strategy for multi-indication drugs has been to stretch indications out over the lifespan of the product. Because of the truncated economic lifespan under the IRA, manufacturers will need to consider strategies to bring value forward earlier in a product’s economic life.

The average time to market for a new molecular entity is 10-13 years of clinical development.2 Spreading research and development costs out over a longer period creates an investment distribution strategy that plays out over decades. With clinical development costs easily surpassing billions of dollars for many molecules, this spreading strategy has created a more robust industry pipeline into high-need patient populations as annual investment costs can be better managed. These dynamics also play out differently in large manufacturers as compared to small or emerging biopharma organizations that must carefully stage their investments.

Under the IRA, manufacturers will now need to accelerate development for multi-indication molecules through indication stacking strategies, meaning that multiple indications will need to be pursued simultaneously rather than sequentially. This compression of research and development spend to occur earlier in the lifespan means that there will be necessary tradeoffs on what gets investigated, when it gets investigated, and how that investigation is funded. The long-term result will be that fewer assets are developed because risk of failure is higher and the intensity of development and funding will have increased. For small and emerging biopharma manufacturers that are not as well funded as larger industry counterparts, stacking of multiple clinical trials to run in parallel may not even be possible due to funding constraints.

Products that were previously viable to pursue will no longer hold the same value

The Net Present Value of an asset is a calculation used by the life sciences industry to evaluate whether the return on research will be positive over the economic life of a drug. The calculations are complex and take many things into account such as estimated time to market, cost of development, likelihood of success, and the forecasted gross and net sales over time. Because of how drug adoption builds over time, peak value occurs late in the product lifecycle.

Altering clinical trial strategy can lengthen time to market as asset priorities change, thereby impacting the value of that asset over its lifetime. The combined effect of policy changes included in the IRA, alongside existing market challenges such as modern launch performance and margin compression, are creating increasingly negative drags on investment dollars. For many molecules, the negative drag will be enough to tip into asset cancellation or de-prioritization, thereby reducing the number of treatments available for patients in the future.

These altering economics effects are not just for branded medications, but will also impact the economics of generic and biosimilar products. Changing the late lifecycle net price the system pays for branded products spills over into the economic incentive for launching a generic or biosimilar version of the molecule. Broadly, lower economic incentives could lead to fewer entrants and have unintended downstream consequences in generic markets.

Will the world ever see another drug like Merck’s Keytruda under the Inflation Reduction Act?

Lilly CEO Dave Ricks recently commented, “I think that we’re going to miss the next Keytruda. And that’s why we’re raising the points that we are.”3 Over Keytruda’s lifespan, Merck has invested over $45 billion into clinical research for the drug. That research has spawned 40 indications for which over 1 million cancer patients have been treated.4 Beyond the direct Keytruda clinical research performed by Merck, there have been many combination treatment trials that other life sciences manufacturers have pursued. Globally, Keytruda is approved in 95 countries.

The practice of evidence-based medicine means that research must be made to establish new standards of care before deploying into patient populations. That evidence takes time and investment to build while strategies take many years to play out. Altering the economic lifespan of a product such as Keytruda could slow research, directly delay patient access to medicine, and have a global health impact.

References:

- https://www.fda.gov/drugs/novel-drug-approvals-fda/new-drug-therapy-approvals-2022#:~:text=Expedited%20Programs%20for%20Serious%20Conditions,Biologics%20License%20Applications%20(BLAs).

- IQVIA Institute.

- https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/asco-were-going-miss-next-keytruda-ceos-lilly-gilead-and-merck-talk-ira-consequences.

- https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/keytruda-leading-way-merck-counts-over-80-possible-oncology-drug-approvals-2028#:~:text=With%20$17.2%20billion%20in%20sales,end%20of%202024%2C%20Oosthuizen%20added.

IQVIA’s Market Access Center of Excellence

In a time when better access has never mattered more, IQVIA has built the largest and most experienced market access team in the industry. That team of experts drives IQVIA’s Market Access Center of Excellence, powered by intelligent connections between data, analytics, technology, and strategy to help clients navigate today’s challenging access environment.

Related solutions

Gain high value access and increase the profitability of your brands