IQVIA is working to advance public health in partnership with other companies, governments, and non-governmental organizations, from fighting opioid addiction to addressing antibiotic resistance.

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the oldest diseases affecting humankind, accounting for 10.8 million cases and killing approximately 1.25 million people in 2023.1 While preventable and curable, TB remains the deadliest infectious disease globally, surpassing COVID-19 and HIV-related deaths combined. More importantly, TB disproportionately affects the most vulnerable and impoverished populations, with an increasingly devastating impact in patients and communities due to comorbidities, drug resistance, pandemics, climate change, conflict, migration, and catastrophic out-of-pocket expenditures for those insufficiently covered by national health schemes.

Notable clinical developments in the last decade have renewed the TB landscape, but more and stronger action is needed to better diagnose, treat, and support people living with TB. In parallel, as deep changes are taking place in the global health architecture in 2025, particularly regarding governance, funding and priorities, it is relevant to review the state of the art of the TB response, reflecting on the most salient issues directly influencing the disease’s trajectory and the last-mile work of civil society and community-based actors.

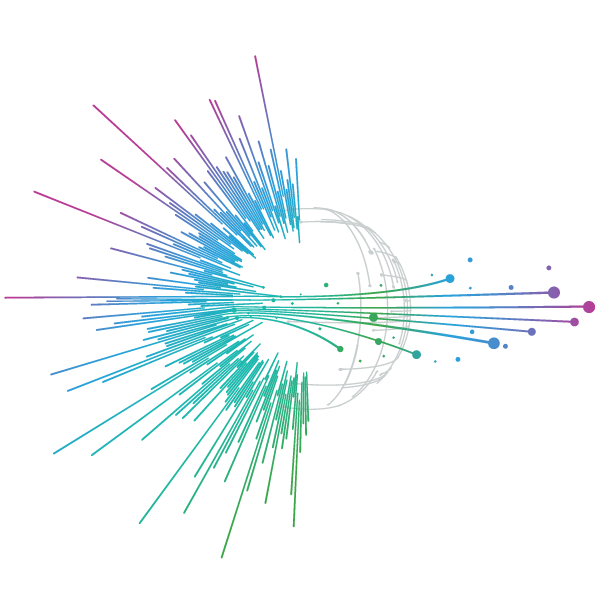

The current pipeline of medicines and vaccines for tuberculosis

In terms of clinical development over the last decade, the optimization of rifamycins in drug-sensitive regimens is promising to shorten the treatment of TB from six to four months.2 For drug-resistant strains, after a stalemate in drug development for 40 years, bedaquiline was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2012,3 followed by several other new compounds such as delamanid and pretomanid in combination with linezolid and bedaquiline. These medicines have led to the recommendation of several all-oral, shorter six- to nine-month regimens.4 Many of these treatments are comprised of three to four drugs, markedly reducing the potential for toxicity and drug-drug interactions and making treatment more tolerable for patients. Likewise, advancements for TB infection have broadened options to shorten treatment from upwards of nine months of daily medications to three months of weekly treatment.5 Six new immunization products in the late phase of development could replace the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, which provides insufficient protection and has been the only TB vaccine available for almost a century.6,7

Despite consequential discoveries in recent years, the microbiological features of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the pathogen responsible for the disease, continue to pose challenges to drug and vaccine development. This bacillus can evade the host’s innate immunity, impede drug penetration due to its waxy cell walls, and prolong the amount of time required for drug efficacy and resistance testing due to its slow growth. Mycobacterium tuberculosis can also mutate and develop drug-resistant strains, which can extend treatment to 18 to 24 months, in contrast to the usual six to nine for drug-sensitive infections.

These steps forward are reassuring, but they are not entirely devoid of obstacles. IQVIA's experience on the ground shows several barriers to TB research and implementation:

- Despite the promising efficacy of bedaquiline-containing regimens, their high cost continues to limit widespread use, particularly in low-income settings. Recent access negotiations are fast-tracking generic alternatives since late 2024 with halved prices in some countries.

- There is a need to expand clinical trial infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa to propel large-scale TB studies, especially in settings of high HIV co-infection.

- New TB vaccine candidates exist, but clinical validation and regulatory approvals take years, delaying impact.

- Current diagnostic tools still have limitations in rural and high-burden settings. Interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA), molecular bacterial load assay-based (MBLA) diagnostics, and nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), which are used to detect TB, can be very helpful but require further validation and/or investments to enable optimal use.

- Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) remains a significant challenge, requiring complex treatment regimens that pose adherence issues. Ensuring timely diagnosis and treatment initiation, as well as patient care through treatment, remains pivotal.

IQVIA’s insights on TB clinical research stem from the work that the company conducts across a variety of geographies, especially low- and middle-income countries, in addition to the various data assets that allow for a better understanding of the healthcare industry.

Overall, continued investment to develop shorter and safer regimens, alongside immunization tools, is necessary to keep the momentum and the TB response on track. It is equally vital to prioritize financial commitments for implementation science to assess outcomes in global TB programs for active case finding, diagnosis, and treatment of all forms of TB.

Existing and emerging challenges

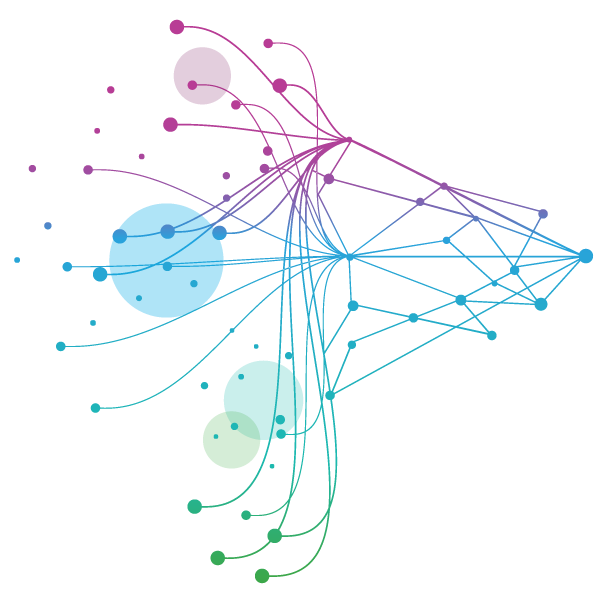

Fighting and eventually eradicating tuberculosis requires continued efforts by a wide range of stakeholders, whose engagement is critical to achieving sustained financing; generate new therapies, diagnostics, and prevention tools; and support adherence and awareness. As with many public health threats, interventions must span across a large continuum of areas whose connection is simply indispensable and unavoidable.

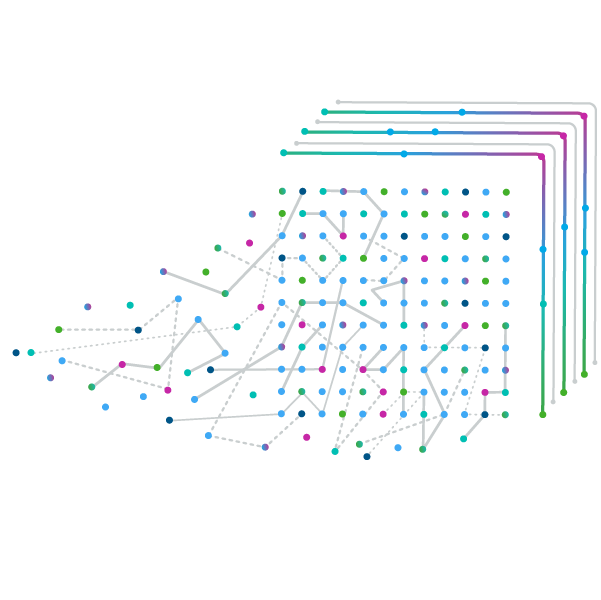

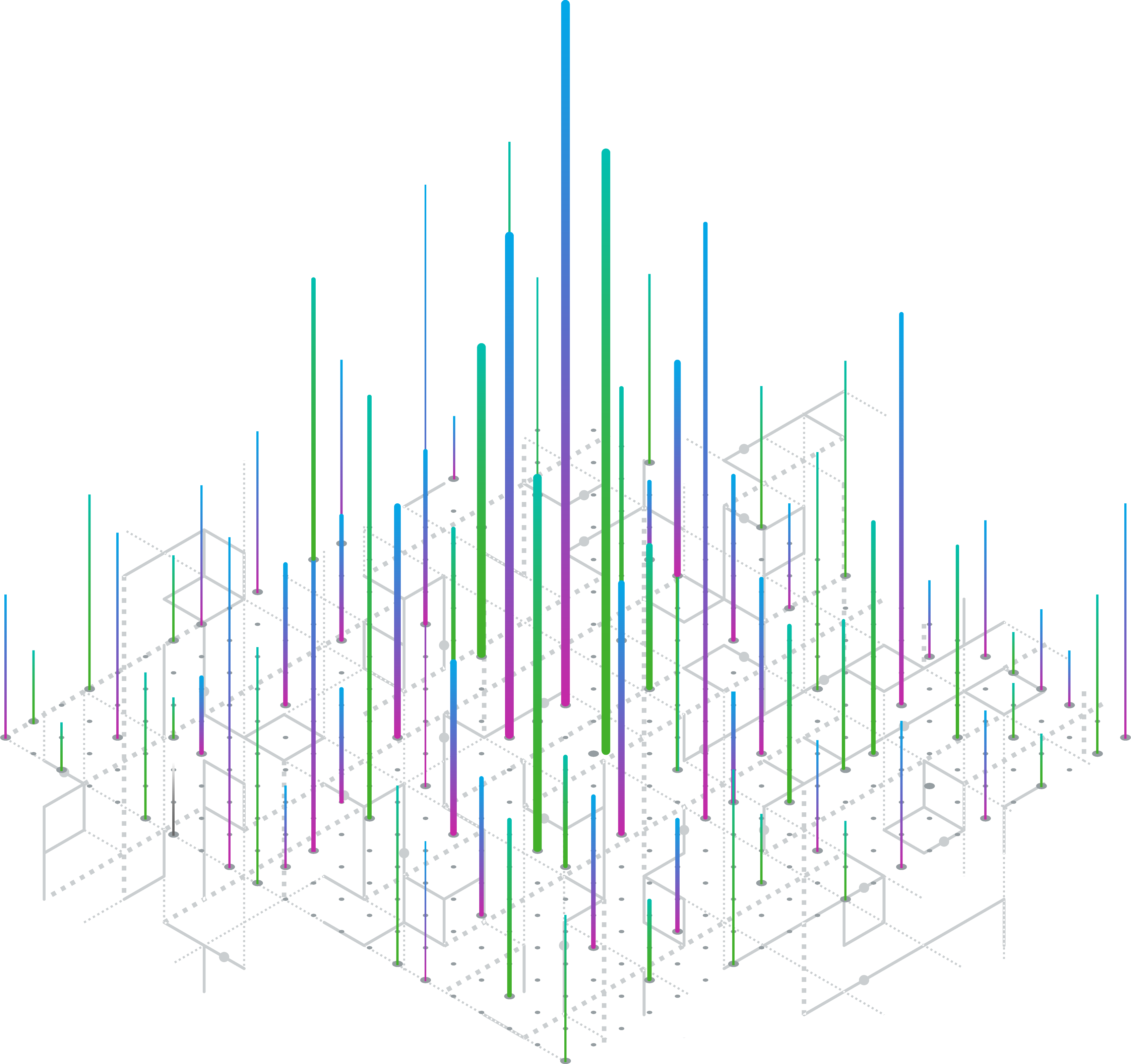

Over the years, many advocacy organizations have signaled the insufficient attention and political commitment that TB has received across a number of dimensions. Progress towards reaching the milestones of the End TB Strategy and the targets set by the 2023 UN High-Level Meeting on TB has not been small, but major gaps are still visible. Although incidence rates were meant to drop around 50% by 2025, compared with 2015, this reduction has not exceeded 8.3%. Also using 2015 as a baseline, TB deaths have only declined by 23%, when the 2025 target aimed for 75%. On the funding side, the mobilization of $22 billion annually to ensure universal access to TB prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care has a deficit of approximately $16.3 billion. Resources for research, expected to reach $5 billion annually by 2027, are falling short by 80%. At this stage, 51% of the population living with TB is incurring catastrophic care costs, exposing extensive disparities in universal health coverage.8

Source: WHO’s Global Tuberculosis Report 2024 (selection of milestones and targets by IQVIA)

In an interview with IQVIA, Ingrid Schoeman, a survivor of extensively drug-resistant TB and Director of TB Proof, a South Africa-based civil society organization, underlined the negative effects that contractions in global health funding are having on TB care. She emphasized the key role that community health workers play in service delivery, but also in increasing awareness around a disease whose public perceptions are heavily shaped by profound stigma, especially when co-infections are part of the picture. Schoeman indicated that “in South Africa, you have people who concluded their treatment over a decade ago and are TB-free but still are not invited to family dinners.” In this context, according to Schoeman, more and better awareness and counseling are essential to close implementation gaps, remove access barriers, and improve care-seeking behaviors. In this regard, she added that “it is important to identify people who are not accessing TB care, especially within high-risk groups. People who had TB in the past two years, close TB contacts, and those living with HIV should all be tested regardless of having symptoms. Therefore, community-led initiatives to raise awareness are extremely important and can encourage high-risk groups and men, who are the most affected population, to seek care.” Schoeman also stressed the importance of factoring in complementary interventions to treatment, including counseling and nutritional needs.

The road ahead: Practical recommendations to step up action

A push to maintain the cadence and strength of TB service delivery and related clinical research is urgent. Given the slow progress towards realizing international TB targets, taking the foot off the gas pedal may jeopardize years of investment and significant achievements in disease control.

The first and most important recommendation is for every stakeholder in the space to leverage partnerships and policy advocacy initiatives to accelerate TB elimination. Using an ‘all-hands-on-deck’ approach, policymakers, research institutions, industry actors, and civil society and community organizations should find innovative ways to collaborate and tailor creative solutions.

On the research front, it is imperative to:

- Conduct clinical trials and generate real-world evidence for optimal TB diagnostics, vaccines, and treatment in countries and communities that are most affected. Maintaining sufficient investment in the full spectrum of research from phase I to implementation science and service delivery diminishes the likelihood of research pipeline gaps.

- Facilitate cost-effectiveness and modeling studies to drive policy changes in TB drug pricing. A recent study identified that treatment with improved TB regimens of shorter duration may yield substantial cost savings, despite relatively higher drug costs of improved TB regimens over the standard of care.9

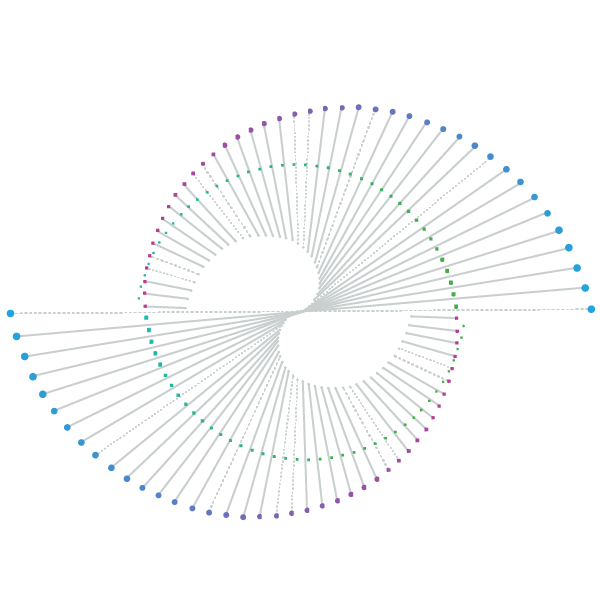

- Strengthen clinical trial networks in Africa to enhance local research capabilities, thereby capturing the manifold genealogical, social, and comorbid conditions of the continent. According to IQVIA studies, only 4% of the total global clinical trials carried out in 2023 took place in Africa, which results in less than 2% of the data analyzed in genomics research originating from the continent.10 This is concerning when considering that many TB high-burden countries (for example, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria, home to almost 8% of new cases globally)11 are located in Africa. Better and more effective therapies and vaccines need population genomic insight, especially in geographies where the disease is more prevalent.

In the frontlines of the TB response, civil society organizations are increasingly:

- Urging governments to increase domestic resource mobilization, stressing that the benefits of TB prevention and care extend beyond the health sector. National health budgets vary broadly and guaranteeing that TB care is properly funded in high-burden countries requires more than a political push for increased allocations. In countries like Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China and South Africa, over 90% of TB financing stems from domestic resources, while dependence on the latter in other high-burden countries outside this group can range between 39% and 48%.12 The goal is to increase or maintain resource flows and to maximize efficiency gains for national health systems through integrated care approaches.

- Considering alternative and diversified sources of funding, especially foundations, multilateral development banks, emerging donors, and the private sector, bearing in mind that these stakeholders cannot entirely or immediately replace the sheer magnitude of public resources traditionally provided to global health. The need to explore alternative sources may invite stakeholders on the ground to think differently and examine interdependencies with other priority areas, but that should not happen at the expense of the values and priorities of TB key populations.

- Leading and fostering partnership opportunities with the private sector to explore innovative solutions, the deployment of blended finance mechanisms, and the design and implementation of access projects, with the aspiration of ultimately driving long-term sustainable solutions.

- Positioning the mandate of relevant TB organizations in new national, regional or international fora, showcasing how their expertise, networks and capabilities can make a difference in the TB response.

References

1 World Health Organization (n.d.). Tuberculosis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

2 World Health Organization (2022). WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: Treatment of drug-susceptible tuberculosis. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240048126

3 Mahajan, R. (2013). Bedaquiline: First FDA-approved tuberculosis drug in 40 years. International Journal of Applied and Basic Medical Research, 3(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-516x.112228

4 See reference 2.

5 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Latent TB infection treatment. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm

6 World Health Organization (2024). Global Tuberculosis Report 2024. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/379339/9789240101531-eng.pdf?sequence=1

7 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Vaccines for healthcare personnel. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/hcp/vaccines/index.html

8 See reference 6.

9 Ryckman, T., Schumacher, S., et al. (2024). Economic implications of novel regimens for tuberculosis treatment in three high-burden countries: a modelling analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 12(6). https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(24)00088-3/fulltext

10 Rickwood, S., Bailey, S. and Mora-Brito, D. (2024, August 13). How scaling up clinical research in Africa can benefit society and the economy. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/08/africa-scaling-up-clinical-research-benefit-society-economy/

11 Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (2024, November 4). TB in Africa: Global report shows successes, but Nigeria and DRC remain important hotspots. https://shorturl.at/efgH2

12 Wells, W., Waseem, S., and Scheening, S. (2024). The intersection of TB and health financing: defining needs and opportunities. Deleted Journal, 1(9), 375-383. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtldopen.24.0324