IQVIA is working to advance public health in partnership with other companies, governments, and non-governmental organizations, from fighting opioid addiction to addressing antibiotic resistance.

Being diagnosed with sickle cell disease (SCD), a hereditary hemoglobin disorder whose traits are present in 5% of the world's population,1 poses significant challenges for those living with it. People with the condition who manage to survive after age five in Africa, a continent carrying up to 80% of SCD's global burden,2 struggle with stigma, disinformation, and severe access issues to healthcare services and therapeutic solutions, many of which continue to be out of reach for patients with limited resources. Because SCD is a treatable condition, the landscape should be de facto different and less burdensome for patients.

During IQVIA's 2023 Africa Health Summit in Kigali,3 a representative from a patient advocacy organization focused on SCD explained that children living with the condition face obstacles that start early on within their own homes: their parents fail to understand the disease and at times blame one another for transmitting it genetically. He pointed out that if the child bypasses the 50% to 80% probability of dying prematurely due to infection or severe anemia,4 growing frail and thin with jaundiced eyes and poor health normally results in discrimination and ostracism. IQVIA research on the role of patient advocacy organizations5 also highlights that both people living with SCD and the family members taking care of them may face financial difficulties due to productivity losses, adding more pressure to the fragile situation of vulnerable groups. A cost-of-illness study published in 2020 estimated that SCD generated approximately US$9.1 billion in annual costs to patients across 11 countries in sub-Saharan Africa.6

Despite its impact on individuals and their communities, collective action to effectively address SCD has historically been underwhelming. As is the case for many diseases, ensuring access to appropriate and sustainable healthcare solutions for SCD is not exempt from major bottlenecks, including substandard to non-existent screening practices, low awareness, lack of insurance coverage, and the inability of affected populations to find and afford critical therapies. To counter these trends and provide the right standard of care, many governments are actively implementing comprehensive SCD programs, most notably Uganda, where 20,000 children are born with sickle cell disease annually,7 and India, where the government launched the National Sickle Cell Elimination Mission in 2023.8

Gaps in data on the prevalence and effects of the disease, including knowledge on population genetics and comorbidities, also hinder the response. A recent study covering 204 countries and territories between 2000 and 2021 illustrates how changes in methodological approaches differentiating all- and single-cause considerations can trigger a substantial increase in morbidity and mortality estimates, raising awareness about the urgency to carefully monitor SCD evolution and care protocols.9 Based on the figures of this study, the number of people living with the diseases increased by 41.4% (or up to 7.74 million globally), with a total disease mortality burden of 376,000 (versus 34,400 cause-specific deaths), 81,100 of which are children under age five. In terms of prevalence, 90% of the world's population affected by SCD is located in Nigeria, Burkina Faso, India, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Ghana.10

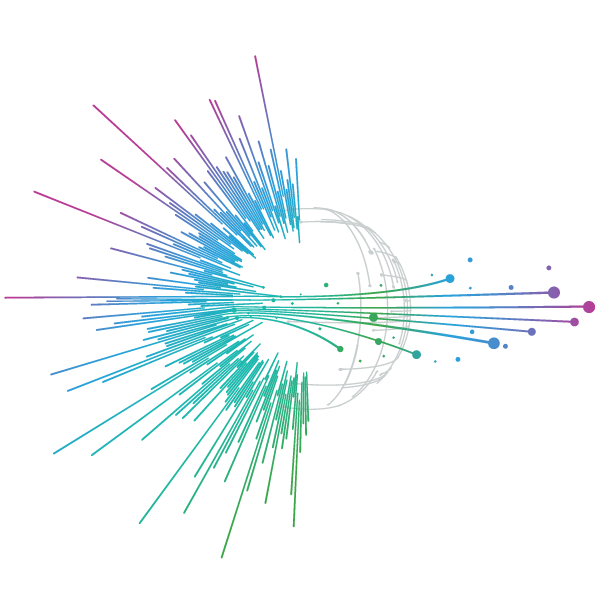

Figure 1: Basic facts about sickle cell disease

Source: Thomson, A. et al. (2023). GBD 2021 Sickle Cell Disease Collaborators

Tackling this multidimensional public health concern is important for two main reasons. First, disease burden is rising in tandem with population growth, with 13.7% more newborn babies since 200011 diagnosed with the disorder. Approximately 230,000 of those children12 are born in African countries where gene traits are present in 20% to 40% of the population. As forecasts indicate, these figures could grow up to 30% globally by 2050,13 acting fast is a clear imperative. Second, the impact of SCD can be reduced through good-quality people-centered care, access to diagnosis, symptomatic relief, and access to disease-modifying drugs.

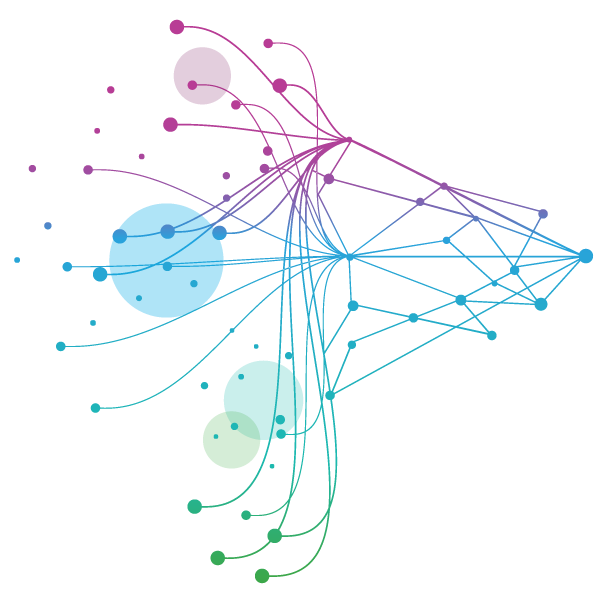

Figure 2: Mortality in Africa per 100,000 people

Source: Thomson, A. et al. (2023). GBD 2021 Sickle Cell Disease Collaborators

Ensuring that SCD receives the attention it deserves from public health stakeholders involves action in six areas:

-

Awareness and education:

The damaging stigma around SCD exists globally at both interpersonal and institutional levels. While the nature of this differs for individuals, the detrimental consequences are similar. Combatting this phenomenon requires educating the public through widespread awareness campaigns and media interventions as well as training healthcare professionals to understand the disease and available treatments. Patient advocacy organizations are central players in this space, making the situation of people living with SCD visible to governments, industry and community stakeholders. Further, promoting health practices that incorporate genetic counselling is widely recommended to help the population identify predispositions to SCD, more specifically in countries with a higher prevalence.

-

Early screening and diagnosis:

Screening saves lives when performed early. Timely diagnosis for newborns is particularly important in SCD, considering the impact of the condition on the life expectancy of children under five. Regardless of age, scaling up point-of-care screening and providing counselling to increase awareness about treatment options is crucial for the successful management of SCD. However, the motivation behind screening needs to be made clear for families, communities and healthcare workers, and initiatives must be introduced to improve access to care, whether this be to basic preventive medications or disease-modifying drugs.

-

Access to comprehensive care:

A key element of advancing access is the integration of SCD-related services within primary care, especially in the context of centers of excellence—or similar models—that offer specialist consultations. As part of this system-wide approach, a skilled and people-driven workforce is necessary to navigate SCD and other hemoglobin disorders, informing patients and their families about the condition, and offering treatment options. At a macro level, advocacy should be geared towards identifying sustainable funding mechanisms to support access to medicine and secure insurance coverage for SCD, also incorporating the condition into the universal health coverage agenda.

-

Availability and affordability of medications and treatment:

Even when an individual can overcome the challenges of geography, stigma and misinformation, the price of hydroxyurea, at present the most accessible disease-modifying drug for SCD, can still be too high for many. Adding this therapy to essential medicine lists could reduce its price and increase its availability, but such results are contingent upon market shaping negotiations underpinned by pooled procurement, other purchasing practices, and manufacturing in the countries and regions where it is most needed. Moving in this direction should also factor in a widespread and systematic capacity building of healthcare workforce to enable adequate prescribing. Finally, innovative approaches such as gene therapy could also make a difference in patient outcomes, but costs will likely be prohibitively high for target populations.

-

Data collection:

Insufficient and poor-quality data—or simply data whose value is not maximized—make it difficult to accurately track SCD incidence, prevalence, morbidity, mortality and treatment outcomes. While figures currently available shed some light on the magnitude of the problem, they are usually disputable and fail to paint a complete picture. Collecting reliable, disaggregated and standardized data through registries and electronic health records can illustrate the life course of people living with SCD. Alongside proper analysis, these practices can inform national policies and health system decisions, identify knowledge gaps, and facilitate the sharing of best practices and lessons learned across countries. Those responsible for health system stewardship need to approach data collection as a continuous process and not as just a one-off occurrence.

-

Clinical research:

Prior to 2017, only hydroxyurea, a recycled chemotherapy drug, was available to treat SCD. Hydroxyurea was approved for SCD in the 1990s, exemplifying the limited medicine research and development pipeline to address this condition over the last few decades. Recent activity around SCD drug development has resulted in approvals for three medicines and two gene therapies. IQVIA is playing a critical role in this process and was involved in two of the three recent approvals, participating in multiple other drug and gene therapy trials for emerging agents. Despite this progress, a sizeable unmet need in SCD still remains as none of the therapies developed to date have completely eliminated related complications and gene therapy approaches are not accessible to the vast majority of people living with the condition. The World Health Organization is conducting medical landscape assessments for gene therapy in Africa to advance research in the field, develop disease control tools, and examine access considerations.14

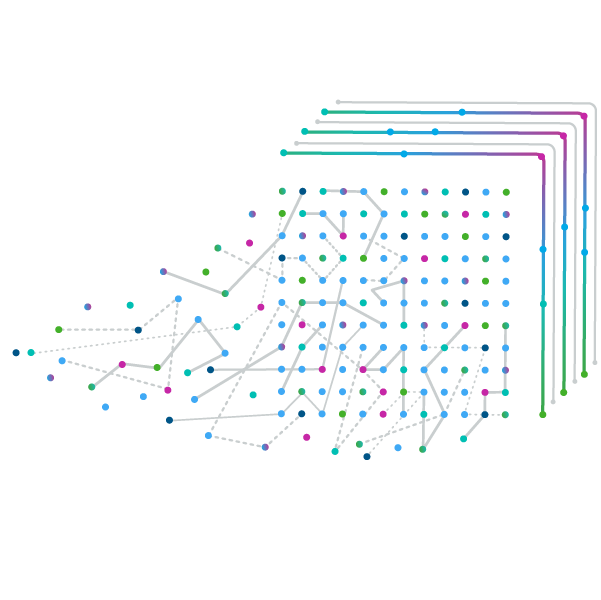

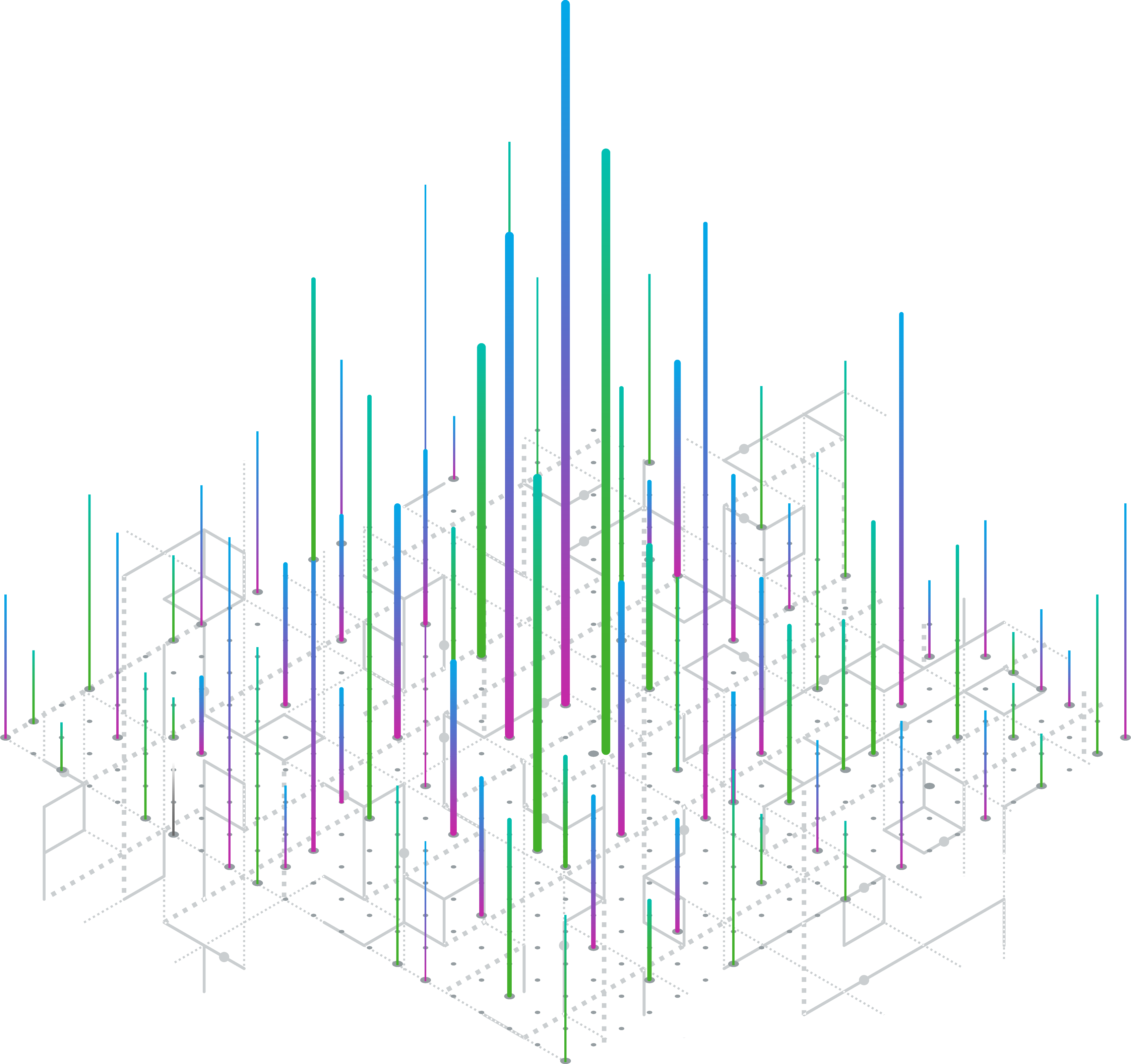

Figure 3: Suggested actions to change the landscape of sickle cell disease

Source: IQVIA’s EMEA Thought Leadership (2024)

This discussion demonstrates that grappling with the societal and healthcare-related complexities of SCD demands harmonized multi-sectoral coordination. Such efforts need to start by increasing collective awareness about the nature of the disorder; ensuring that health systems provide affordable and accessible treatment; filling funding gaps in a sustainable fashion; delivering the right infrastructure; and finalizing national and international guidelines that serve as foundations for service design. Similarly, patient advocates and other key stakeholders need to be supported in their work to continue positioning SCD on the public health agenda, while governments should be encouraged to keep SCD as a priority to allow much needed structural changes in health systems to take place.

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Jeffrey Keefer, Senior Vice President, Therapeutic Strategy; Helena Bayley, Analyst, EMEA Thought Leadership; and Romilly Travers, Intern, EMEA Thought Leadership.

1 World Health Organization (2024, June 12). Sickle cell disease [Fact sheet]. Africa Region. https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/sickle-cell-disease

2 Adigwe, O. et al. (2023). A critical review of sickle cell disease burden and challenges in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Blood Medicine, 14: 367-376. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10239624/

3 Mora-Brito, D. (2024). IQVIA Africa Health Summit [Report]. IQVIA EMEA Thought Leadership. https://www.iqvia.com/locations/middle-east-and-africa/library/brochures/africa-health-summit

4 Moeti, M. et al. (2023). Ending the burden of sickle cell disease in Africa. The Lancet Haematology. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(23)00120-5

5 Madelung, M. et al. (2023). Climbing the mountain one step at a time: How patient organizations in Africa are advancing healthcare [White paper]. IQVIA, EMEA Thought Leadership. https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/mea/white-paper/iqvia-patient-organizationsin-africa-white-paper.pdf

6 The Economist (2020). Assessing the burden of sickle cell disease in sub-Saharan Africa. A cost of illness study. https://pages.eiu.com/rs/753-RIQ-438/images/EIU%20Healthcare%20-%20Sickle%20cell%20disease%20in%20Africa%20report%20V5%20%281%29.pdf

7 Ndeezi, G. et al. (2016). Burden of sickle cell trait and disease in the Uganda Sickle Surveillance Study (US3): A cross-sectional study. Lancet Global Health 4(3): e195-200. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26833239/#:~:text=Background%3A%20Sickle%20cell%20disease%20contributes,accurate%20data%20are%20not%20available

8 Government of India (2024, June 12). National Sickle Cell Anaemia Elimination Mission. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and Ministry of Tribal Affairs. https://sickle.nhm.gov.in/home/about

9 Thomson, A et al. (2023). Global, regional and national prevalence and mortality burden of sickle cell disease, 2000-2021. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/library/global-regional-and-national-prevalence-and-mortality-burden-sickle-cell#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20people%20living,9%C2%B72)%20in%202021.

10 See reference 2.

11 See reference 9.

12 Simpson, S. (2019). Sickle cell disease: A new era [Comment]. The Lancet. https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lanhae/PIIS2352-3026(19)30111-5.pdf

13 Piel, F. et al. (2013). Global burden of sick cell anaemia in children under 5, 2010-2050: Modelling based on demographics, excess, mortality and interventions. PLOS Medicine, 10(7): e1001484. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23874164/

14 See reference 4.