-

Americas

-

Asia & Oceania

-

A-I

J-Z

EMEA Thought Leadership

Developing IQVIA’s positions on key trends in the pharma and life sciences industries, with a focus on EMEA.

Learn more -

Middle East & Africa

EMEA Thought Leadership

Developing IQVIA’s positions on key trends in the pharma and life sciences industries, with a focus on EMEA.

Learn more

Regions

-

Americas

-

Asia & Oceania

-

Europe

-

Middle East & Africa

-

Americas

-

Asia & Oceania

-

Europe

Europe

- Adriatic

- Belgium

- Bulgaria

- Czech Republic

- Deutschland

- España

- France

- Greece

- Hungary

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italia

EMEA Thought Leadership

Developing IQVIA’s positions on key trends in the pharma and life sciences industries, with a focus on EMEA.

Learn more -

Middle East & Africa

EMEA Thought Leadership

Developing IQVIA’s positions on key trends in the pharma and life sciences industries, with a focus on EMEA.

Learn more

SOLUTIONS

-

Research & Development

-

Real World Evidence

-

Commercialization

-

Safety & Regulatory Compliance

-

Technologies

LIFE SCIENCE SEGMENTS

HEALTHCARE SEGMENTS

- Information Partner Services

- Financial Institutions

- Global Health

- Government

- Patient Associations

- Payers

- Providers

THERAPEUTIC AREAS

- Cardiovascular

- Cell and Gene Therapy

- Central Nervous System

- GI & Hepatology

- Infectious Diseases and Vaccines

- Oncology & Hematology

- Pediatrics

- Rare Diseases

- View All

Impacting People's Lives

"We strive to help improve outcomes and create a healthier, more sustainable world for people everywhere.

LEARN MORE

Harness the power to transform clinical development

Reimagine clinical development by intelligently connecting data, technology, and analytics to optimize your trials. The result? Faster decision making and reduced risk so you can deliver life-changing therapies faster.

Research & Development OverviewResearch & Development Quick Links

Real World Evidence. Real Confidence. Real Results.

Generate and disseminate evidence that answers crucial clinical, regulatory and commercial questions, enabling you to drive smarter decisions and meet your stakeholder needs with confidence.

REAL WORLD EVIDENCE OVERVIEWReal World Evidence Quick Links

See markets more clearly. Opportunities more often.

Elevate commercial models with precision and speed using AI-driven analytics and technology that illuminate hidden insights in data.

COMMERCIALIZATION OVERVIEWCommercialization Quick Links

Service driven. Tech-enabled. Integrated compliance.

Orchestrate your success across the complete compliance lifecycle with best-in-class services and solutions for safety, regulatory, quality and medical information.

COMPLIANCE OVERVIEWSafety & Regulatory Compliance Quick Links

Intelligence that transforms life sciences end-to-end.

When your destination is a healthier world, making intelligent connections between data, technology, and services is your roadmap.

TECHNOLOGIES OVERVIEWTechnology Quick Links

CLINICAL PRODUCTS

COMMERCIAL PRODUCTS

COMPLIANCE, SAFETY, REG PRODUCTS

BLOGS, WHITE PAPERS & CASE STUDIES

Explore our library of insights, thought leadership, and the latest topics & trends in healthcare.

DISCOVER INSIGHTSTHE IQVIA INSTITUTE

An in-depth exploration of the global healthcare ecosystem with timely research, insightful analysis, and scientific expertise.

SEE LATEST REPORTSFEATURED INNOVATIONS

-

IQVIA Connected Intelligence™

-

IQVIA Healthcare-grade AI®

-

-

Human Data Science Cloud

-

IQVIA Innovation Hub

-

Decentralized Trials

-

Patient Experience Solutions with Apple devices

WHO WE ARE

- Our Story

- Our Impact

- Commitment to Global Health

- Code of Conduct

- Sustainability

- Privacy

- Executive Team

NEWS & RESOURCES

Unlock your potential to drive healthcare forward

By making intelligent connections between your needs, our capabilities, and the healthcare ecosystem, we can help you be more agile, accelerate results, and improve patient outcomes.

LEARN MORE

IQVIA AI is Healthcare-grade AI

Building on a rich history of developing AI for healthcare, IQVIA AI connects the right data, technology, and expertise to address the unique needs of healthcare. It's what we call Healthcare-grade AI.

LEARN MORE

Your healthcare data deserves more than just a cloud.

The IQVIA Human Data Science Cloud is our unique capability designed to enable healthcare-grade analytics, tools, and data management solutions to deliver fit-for-purpose global data at scale.

LEARN MORE

Innovations make an impact when bold ideas meet powerful partnerships

The IQVIA Innovation Hub connects start-ups with the extensive IQVIA network of assets, resources, clients, and partners. Together, we can help lead the future of healthcare with the extensive IQVIA network of assets, resources, clients, and partners.

LEARN MORE

Proven, faster DCT solutions

IQVIA Decentralized Trials deliver purpose-built clinical services and technologies that engage the right patients wherever they are. Our hybrid and fully virtual solutions have been used more than any others.

LEARN MORE

IQVIA Patient Experience Solutions with Apple devices

Empowering patients to personalize their healthcare and connecting them to caregivers has the potential to change the care delivery paradigm.

LEARN MOREIQVIA Careers

Featured Careers

Stay Connected

WE'RE HIRING

"At IQVIA your potential has no limits. We thrive on bold ideas and fearless innovation. Join us in reimagining what’s possible.

VIEW ROLES- Blogs

- Emerging and Established Biopharma Renegotiate the Value of Clinical Innovation

Emerging biopharma (EBP) companies are proving to be a disruptive force in pharmaceutical innovation, having developed the vast majority of the late-stage pipeline in Next-Generation Biotherapeutics, cumulatively representing immense commercial potential. But in a market with such high reward and high risk, the entire ecosystem is renegotiating the value of EBP innovations and reappraising how best to commercialize them.

This renegotiation is one focus of an IQVIA Institute report - Emerging Biopharma’s Contribution to Innovation. The report not only documents the scope and scale of EBP pharmaceutical innovations, but goes further to expose trends in how EBPs, their investors and established pharma are navigating a new commercial ecosystem.

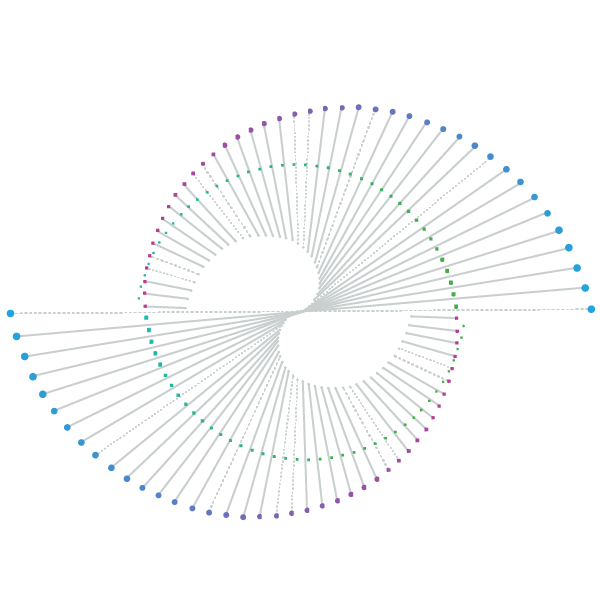

In the last ten years, EBPs have developed more than 90% of the late-stage pipeline in Next-Generation Biotherapeutics across a wide range of treatment areas, and account for 80% of total R&D activity. Their success has made them attractive targets for acquisition, partnership and investment (see exhibit). Investor interest in EBPs has reached an all-time high, with U.S. venture-capital activity seeing a sharp increase over the past five years.

The increase in pipeline share is not only from the EBP’s focus on the fastest-growing areas of oncology and orphan drugs, but also because they are increasingly able to develop and market their own innovations without the need to partner or be acquired. As a result, some of the assumptions about how EBP innovations become commercial products are being challenged. The historical dependence of emerging biopharma on big pharma is lessening.

Emerging biopharma companies assume more R&D responsibility

Emerging biopharma companies have often relied in collaboration with established pharma in R&D activities. Our report shows a trend toward fewer such deals with a higher total value, perhaps reflecting more caution about sharing risk at an early stage.

Instead of these collaborative deals, some big pharma firms prefer to fund early-stage EBP research via option-based deals that leave the R&D in the hands of the biotech company until a defined point in development. Like collaborative R&D deals, these agreements are usually high in total value but heavily backloaded.

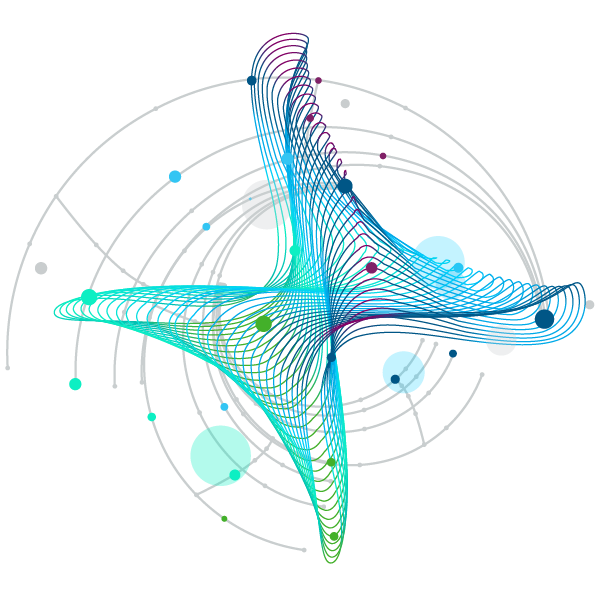

Increasingly, emerging biopharma companies run their own trials

From 2010 to 2018, the number of clinical trials run by EBPs has more than doubled, and now represent 65% of trials started in 2018. The increase is broad, across all therapy areas, but is most significant in endocrinology, psychiatry, respiratory, rheumatology and transplantation (see exhibit).

Emerging biopharma companies are even conducting more oncology trials, which tend to be more complex and require more resources. In 2018, the EBP share of oncology trials increased to 65%, up from 43% in 2010.

Despite the challenges, emerging biopharma companies now have a composite success rate that is almost 5% higher than other company segments.

Emerging biopharma companies launch more of their own innovations

Some of the most successful new drugs of the past five years were discovered by emerging biopharma companies and later launched by larger companies. Certainly, in the past, the majority of EBP assets were sold or licensed before launch. But in 2018, EBPs originated and launched 42% of new drugs in 2018, up from 26% in 2017. EBPs are retaining and launching more of the product they originate, launching 55% of originated products from 2013-2018, compared to 41% in the five years prior to 2013.

The steady growth of EBP launches, compared to the more variable number of big pharma launches over the past few years, reflects their significant share of the pipeline and a greater level of strategic interest in marketing their assets themselves.

EBP-originated products generally reach the market faster if they were acquired. In particular, assets that were initially owned by an EBP but submitted and subsequently launched by big pharma spent less time in development compared to those owned, developed and launched by an EBP.

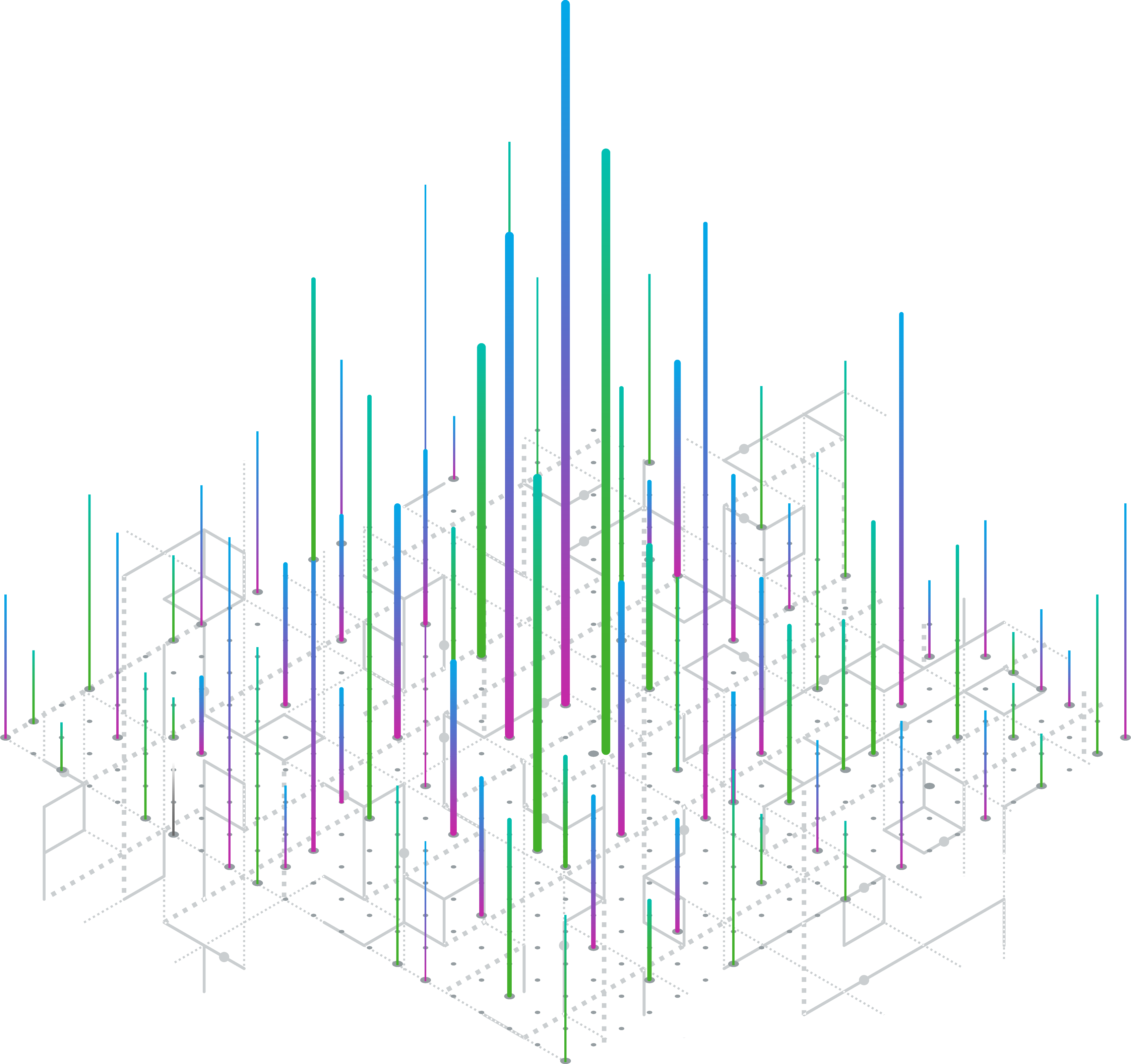

Emerging biopharma companies generally achieve lower average sales when launching new active substances than other companies (see exhibit).

Average quarterly sales uptake at one year after launch is 2.6 times higher for larger companies launching emerging biopharma-originated products than for emerging biopharma companies who develop and launch their own assets, widening to 6.5 times higher 18 months later.

EBPs will not be forever emerging

Despite the challenges EBPs face in developing their treatments and finding a path to market, at least some are likely to stop “emerging” and become one of the dominate big pharma companies. Of the 168 emerging biopharma startups that first received funding in 2008, five have gone public and have achieved market capitalization above $1 billion.

Who will be the next big pharma companies of 2028?

As the IQVIA Institute research indicates, emerging biopharma companies are blazing their own non-traditional trails to success. Using trends such as digital health, predictive analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), biomarkers, and new recruitment models, the innovative and resourceful EBP can better compete with, and possibly become, big pharma.