It is projected that by 2035, nearly 2 billion people will be obese, representing approximately 25% of the world’s population across various ages, sex, race, and ethnicities1. A large number of clinical trials for new treatments aiming to tackle obesity are currently underway, with 157 assets currently spanning phases I-III2. Competition is therefore high, with new anti-obesity medications (AOMs) battling for market access and share of a rapidly growing private market, and the public market, vying for reimbursement, underpinned by evidence of positive outcomes in treated populations.

In order to compete, rigour in evidence is essential through ensuring clinical trials are of appropriate size and duration and include populations representative of clinical practice. Real-world studies, in parallel, are utilised to address gaps, deliver on local evidence needs and where necessary, further contextualise populations to ensure representativity. This is particularly vital in understanding increasingly complex obese populations, defined by measures beyond BMI, and with a growing prevalence of obesity-related comorbidities3.

Analysis of major obesity trial populations

Recent draft guidance published by the FDA in January 2025 for developing drugs and biological products for weight reduction to establish standards for clinical trials, stipulates that clinical trials need to reflect the age, sex, race, and ethnicity of obese populations in clinical practice for the US population4.

An analysis of major obesity trials was conducted to understand the representativity of recruited populations. Seven trials each recruited over 1,000 participants: Novo Nordisk’s SELECT, SCALE, FLOW, STEP 1, and STEP 2; and Lilly’s SURPASS trial and SURMOUNT-CVOT (Figure 1). These trials measure the effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists (or tirzepatide, a dual GIP-GLP-1 receptor co-agonist) on weight loss in overweight or obese population or related comorbid populations. The analysis, however, found that the recruited trial populations are not representative of the US obese population5,6,7. Of course, the agents in these trials are not being developed for the US population alone, but the US is, and is likely to remain, the single biggest commercial opportunity for AOMs, with recent regulatory draft guidance proposing that trial demographics should reflect the US obese population. Whilst it is possible to compare trial populations for age and sex to demographics outside of the US and UK, it is unfortunately not possible to compare race demographics in other EU countries due to sensitivity in reporting and collecting of these data8.

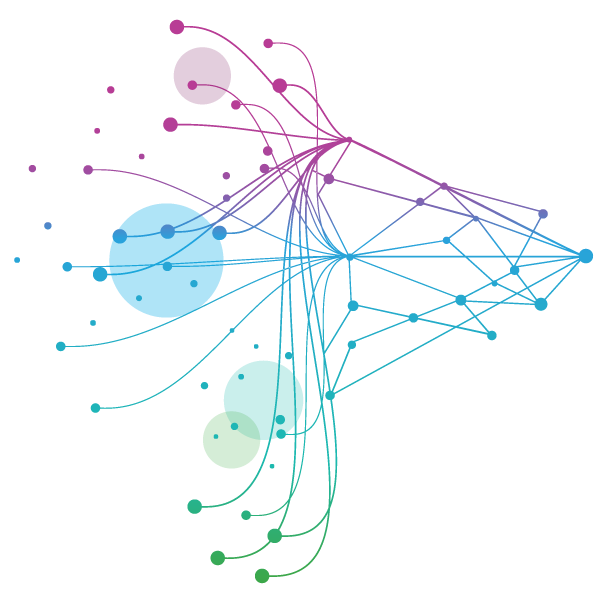

Adults aged 45-54 represent 39.2% of the US obese population9. The mean age across the trials varied from 45 to 67 with only three trials capturing a mean that falls within the US demographic (SCALE, SURMOUNT-1, STEP 1) (Figure 2).

Of the large obesity trials, three trials are disproportionately weighted towards females (SCALE, SURMOUNT-1, STEP 1) whilst three are disproportionally weighted towards males (SELECT, SURPASS-CVOT, FLOW). It is possible to speculate that populations recruited into SELECT and SURPASS-CVOT trials may have been proportionately skewed towards males, in investigating intervention of weight loss in cardiovascular disease, to mimic the higher prevalence of males in each age stratum until after 75 years of age within the US population10.

Black participants are underrepresented, whilst Asian populations are overrepresented relative to the US population. This is consistent across all trials reporting a breakdown of race amongst recruited participants (Figure 4). The SURPASS-CVOT does not provide a breakdown of the race of the recruited trial participants.

The implications of these findings on the mismatch between clinical trial populations and real-world populations for obesity are two-fold: first, clinical trial recruitment must be managed to reflect real world obese populations. This may become an FDA requirement for US approvals, and if so, would drive a need to reach out to certain populations to improve recruitment, as well as being mindful of sex and age distributions in trials. Of course, it is not possible to create high population, late-phase trials to reflect the demographies of the obese populations of all countries however, even though the issue is likely to be further exacerbated when these agents are approved, and widely used, outside of the US and Europe, in the Middle East, Asia, South America and Africa. It is important, with growing use of these agents, that their relevance to, and impact in, country populations be followed through to real world studies to confirm and supplement the findings of clinical trials.

The role of real-world evidence

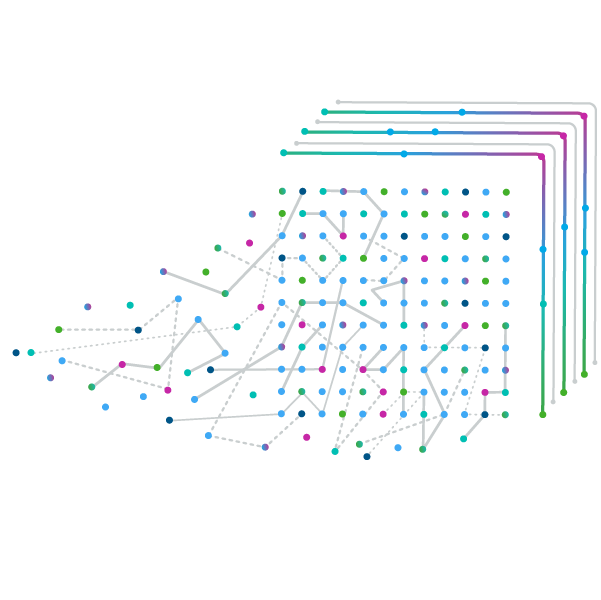

Real-world data (RWD) are data routinely collected as part of healthcare delivery from a variety of sources11. Examples of RWD include data derived from sources such as electronic health records (EHRs), medical claims data and patient-generated sources, from questionnaires completed by patients through to sources of passive data including wearable watches or fitness devices. Figure 5 shows the range of RWD sources that can be compiled and used to generate insights on patients beyond data collected during clinical trials. This broad range of data sources is perhaps uniquely important in understanding obesity, as a disease heavily governed by lifestyle factors measured by wearable devices and symptoms, both emotional and physical, reported directly by the patient. RWD provides information for cohorts of patients with typically less stringent restrictions to cohort inclusion/exclusion criteria allowing for a more representative view of the population including age, sex, race, and presence of comorbidities.

Real-world evidence (RWE), generated from RWD, is increasingly being used across the product life cycle from early clinical development in identifying unmet need and informing clinical trial design through to market access, payer negotiations and labelling expansion (Figure 6). In a competitive and fast-paced market such as obesity, accuracy, and rigour of evidence through representative real-world populations is essential in ensuring drug development efficiency, demonstrating value to payers, and ensuring long-term safety and effectiveness of treatments.

RWE steps in where clinical trials often fall short. The nature of RWD allows for capture of the high complexity, numerous interdependent cardiovascular and metabolic (CV-met) comorbidities seen in obese populations. The ability to micro-segment these populations by their CV-met risk factor dimensions is key to ensuring differentiation of AOMs in an increasingly crowded market12.

Real-world data in obesity

Sources of RWD have varying strengths and subsequently, different use cases. EHRs, primarily collected for the delivery of clinical care, for example, may be repurposed for use in real-world studies, providing rich clinical data including diagnoses, lab results, prescriptions, and medical history, whilst claims data, routinely collected for medical billing, can provide large-scale treatment data covering broad populations, although may lack some clinical detail. These sources can provide longitudinal data for large numbers of patients, representative of real-world populations, in a cost-effective manner. Contrasting sources such as mobile apps and wearable devices can provide a unique source of data capturing the patient voice, either through active participation in questionnaires or surveys or through passive data collection, e.g., via fitness devices or biosensors. A combination of these data sources may be utilised to follow the entire patient journey, navigating a complex pathway from diagnosis through to treatment, of not only obesity but the wealth of comorbidities that come with it.

RWD, however, is not without its challenges. Obesity is routinely defined by a Body Mass Index (BMI) of greater than or equal to 30 although this may vary by market-specific guidelines13. BMI, and its derivatives (weight and height) are, however, not always routinely, nor longitudinally, captured in clinical practice14,15,16. A study conducted in Germany using the IQVIA Disease Analyzer EHR database assessed the prevalence of BMI documentation by general practitioners (GPs) and found that BMI was recorded for only 10.8% of patients14. It was found, however, that older age and the presence of obesity and type 2 diabetes strongly increased the likelihood of recording this information, but this lack of completeness still presents a barrier for the use of RWD.

Beyond BMI and weight, there are further challenges in the collection and completeness of RWD that need to be overcome. Collection of race and ethnic data is contested in a number of EU markets, whereby these data are considered sensitive or in cases, ‘prohibited [for collection] with exceptions’. Discrepancies in, and lack of recording of, ethnicity and race in RWD in EU countries therefore makes comparison and understanding of real-world populations suffering from obesity challenging in respect to ensuring representativity8. This is becoming an even greater hurdle in assessing treatment initiation of AOMs, with some ethnic minority backgrounds prone to increased risk of chronic weight-related health conditions at a lower BMI due to a higher prevalence of central adiposity17.

The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology commission recommends classifying obesity beyond BMI alone. The recent commission proposes a diagnosis of pre-clinical obesity based on an inclusion of a direct measurement of body fat e.g., via Bone Density (DEXA scans), or further anthropometrics e.g., waist circumference, and clinical obesity as BMI with organ dysfunction or limitations of daily activities18. A further hurdle for RWD, with these metrics rarely being routinely available in sources of data such as EHR, often hidden in unstructured notes or needing to be sourced directly from the patient.

Mobile apps and wearable devices that capture data directly from patients are becoming more commonly adopted and can open up access to a wealth of data that is typically not well captured in more traditional sources of RWD19. This data, such as symptoms, quality of life, measures of anthropometrics beyond BMI and treatment adherence, is of growing importance in the field of obesity and may be pivotal in navigating the evolving market landscape and in design and differentiation of AOMs. Despite its value, this data is not without biases, which need to be acknowledged and addressed. Populations of patients using these devices are potentially younger, wealthier, and more active, already engaging with fitness apps to proactively lose weight and manage their health20,21. A 2022 review published in The Lancet Digital Health, of demographic characteristics of participants in studies using their own devices, found that it leads to preferential enrolment of White participants compared with participants from minority groups22.

Final thoughts

- Real world data can be used across the product life cycle, from optimising clinical trial design and ensuring representative recruitment to informing payer renegotiations

- There are still a number of challenges in collection and use of representative RWD that need to be addressed and overcome in order for this data to truly meet the evidence needs of the evolving obesity market

- As recommendations from recent FDA draft guidance and The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology Commission are disseminated and adopted, capture of vital endpoints, including further anthropometrics of weight beyond BMI and patient-reported data such as limitation of daily activities, may become prioritised in routine clinical care, improving widespread access to this data for research

- Mobile apps, such as Oviva and Second Nature, linked with wearable devices, are becoming increasingly prescribed and reimbursed by healthcare systems which is likely to see them reaching a wider and more diverse population beyond those proactively engaging in health and weight loss23

- Lilly’s recent announcement of a strategic partnership with Health Innovation Manchester to run SURMOUNT-REAL, a 5-year study to evaluate the real-world effectiveness of tirzepatide, could highlight the direction required of RWD generation to overcome existing challenges and ensure rigour in design and collection of RWE, through public-private partnerships and multi-stakeholder engagement with providers across academia, clinical and e-health24.

Call to action: In order to succeed in a competitive and crowed obesity market, innovators must embrace RWE alongside representative clinical trials. Early integrated evidence generation planning can ensure timely use of RWE throughout the product journey to harness value from evidence, in an increasingly complex obesity market, where clinical trials cannot always provide the full picture of the relevance and utility of AOMs for all populations of users.

References

- World Obesity Federation, March 2023: Economic impact of overweight and obesity to surpass $4 trillion by 2035 | World Obesity Federation

- IQVIA Analytics Link

- IQVIA blog, How the Lancet Commission and FDA are moving the goal posts in obesity, January 2025: How the Lancet Commission and FDA are moving the goal posts in obesity - IQVIA

- FDA, Obesity and Overweight: Developing Drugs and Biological Products for Weight Reduction Guidance for Industry, January 2025: Obesity and Overweight: Developing Drugs and Biological Products for Weight Reduction

- World Obesity Federation, March 2024: Data tables | World Obesity Federation Global Obesity Observatory

- National Center for Health Statistics, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2017–2018: Overweight & Obesity Statistics - NIDDK

- United States Census Bureau, 2024: U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States

- Farkas, L. 2017: data_collection_in_the_field_of_ethnicity.pdf

- CDC, September 2024: Adult Obesity Prevalence Maps | Obesity | CDC

- Mosca, L., Barrett-Connor, E. & Wenger, N., November 2011: Sex/Gender Differences in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention | Circulation

- FDA, Framework for FDA’s Real-World Evidence Program, 2018: https://www.fda.gov/media/120060/download

- IQVIA blog, When the dust settles: The future shape of the obesity market, May 2024: When the dust settles: The future shape of the obesity market - IQVIA

- World Health Organisation, March 2024: Obesity and overweight

- Orozco-Ruiz, X., Sarabhai, T. & Kostev, K., Annual prevalence, and factors associated with body mass index documentation in German general practices-A retrospective cross-sectional study, Diabetes Obes Metab, February 2025: Annual prevalence and factors associated with body mass index documentation in German general practices-A retrospective cross-sectional study - PubMed

- Nicholson, B.D., Aveyard, P., Bankhead, C.R. et al., Determinants and extent of weight recording in UK primary care: an analysis of 5 million adults’ electronic health records from 2000 to 2017, BMC Med, November 2019. Determinants and extent of weight recording in UK primary care: an analysis of 5 million adults’ electronic health records from 2000 to 2017 | BMC Medicine | Full Text

- Verberne, L., Nielen, M., Leemrijse, C., Verheij, R., Friele, R., Recording of weight in electronic health records: an observational study in general practice, BMC Fam Pract, November 2018: Recording of weight in electronic health records: an observational study in general practice | BMC Primary Care

- NICE guidelines, January 2025: Identifying and assessing overweight, obesity and central adiposity | Overweight and obesity management | Guidance | NICE)

- F. Rubino et al., Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity, The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, January 2025: Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity - The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology

- IQVIA blog, Digital Solutions for Obesity: Revolutionising Care and Management, January 2025: Digital Solutions for Obesity: Revolutionising Care and Management - IQVIA

- Burford, K., Golaszewski, N.M., Bartholomew, J., "I shy away from them because they are very identifiable": A qualitative study exploring user and non-user's perceptions of wearable activity trackers, Digital Health, November 2021: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8606926

- Gulati, A., Lobo, R., N, N., Bhat, V., Bora, N., K, V., Sinha, M.K., Young Adults Journey with Digital Fitness Tools-A Qualitative Study on Use of Fitness Tracking Device, October 2024: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11555328/#sec12

- Zinzuwadia, A., Singh, J., Wearable devices—addressing bias and inequity, The Lancet Digital Health, December 2022: Wearable devices—addressing bias and inequity - ScienceDirect

- NHS England, NHS Digital Weight Management Programme, Accessed February 2025: https://www.england.nhs.uk/digital-weight-management/nhs-digital-weight-management-programme/#:~:text=It%20can%20be%20hard%20to,NHS%20Foundation%20Trust%20in%20Torquay

- Health Innovation Manchester, October 2024: Greater Manchester plans to partner with industry on a new study to deepen understanding of a weight loss medication - Health Innovation Manchester