Key points:

- The EU funds €10s of billions of health and digital health initiatives though its fiscal programs and influences much more.

- These are complex, with priorities and recipients decided at the EU, national and regional level.

- Health stakeholders should be aware of these and shape their future design.

National government expenditure across the European Union (EU) totals over €7 trillion per annum. Deciding how this money is spent has an enormous impact on citizens' health, since healthcare in the EU is largely publicly funded and represents over 15% of this government expenditure. Yet decisions on government expenditure as a whole, or “fiscal governance”, tend to be made in national finance ministries where healthcare has been seen as a cost to contain, rather than an investment. In the wake of the financial crises and with the growth of the Eurozone, the EU has gained more and more power to influence spending to ensure it aligns with EU priorities and does not jeopardise stability of the monetary union. How the EU treats health expenditure from a fiscal perspective affects the lifeblood of its healthcare.

The EU has several fiscal governance mechanisms for oversight and influence, as well as tools to directly finance expenditure itself. These include the European Semester, the Recovery and Resilience Funds, the Cohesion Policy Funds and the European Investment Bank. These tools all direct spending towards EU priorities, which include improving healthcare and, overlapping this, digitalisation.

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it”

- Peter Drucker.

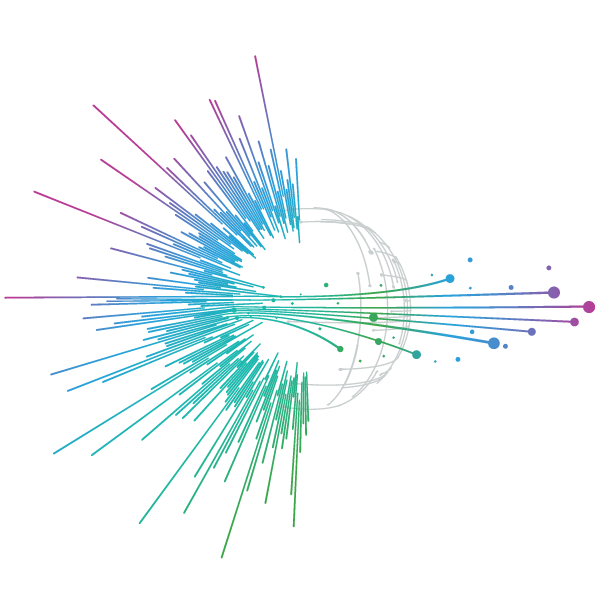

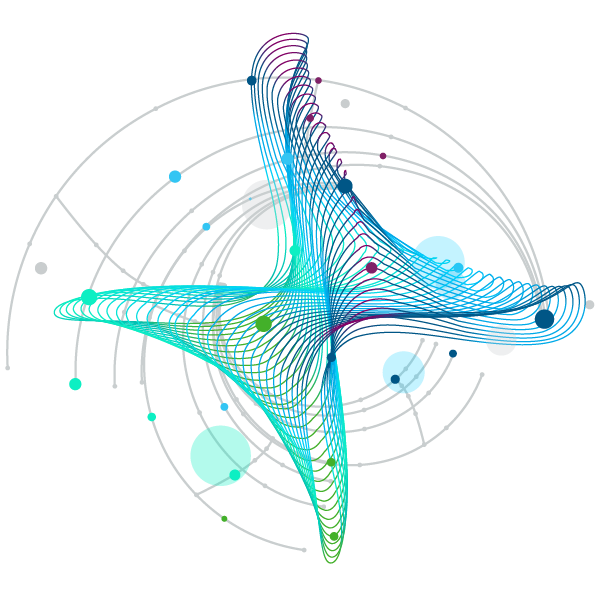

Figure 1. Predicted compound annual growth rate of data created, captured, and replicated by sector.

Source: ‘The Digitization of the World – From Edge to Core’, 2018. International Data Corporation, White Paper # US44413318.

Notes: These are predictions and should be seen as indicative only.

Digitalisation and healthcare are increasingly intertwined. Healthcare generates the largest volume of data of any sector and practitioners are becoming more skilled at using it to inform decisions (see Fig 1). This data is also a growing resource for innovation, and Member States (MS) are increasingly funding initiatives to interlink and use this data. IQVIA has analysed the digital readiness of countries' healthcare systems, with many MS lacking infrastructure or utilizationa, and at very different stages of digital maturity. The extent to which the EU’s fiscal governance mechanisms have featured digitalisation of healthcare hasn’t been explored, to date. This paper examines and explains the EU’s core fiscal governance mechanisms and the extent to which they impact health and digital health.

European Semester

The main fiscal governance tool of the EU is the Semester process, an annual cycle to oversee and steer MS’s budgeting and socio-economic policies, including health:

Originally the European Semester was designed to achieve fiscal prudence, with health underrepresented and seen purely as a cost. However, in recent years health actors such as DG SANTE have greater involvement and so the Semester process places a greater emphasis on healthcare expenditure, with heath and health systems analysis published in the country reports.

Unsurprisingly, in the 2020-2021 European Semester, the focus on health surged in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was the first year that all 27 MS received health-related CSRs (Country -specific recommendations). These ranged from COVID-19 care funding to general health workforce measures and e-health infrastructure. However, an analysis of the 2022 European Semester by EuroHealthNet found that “most countries received energy-related CSRs, while health-related CSRs disappeared almost entirely”.

“The shift in priorities in the CSRs between 2020 and 2022 reflects the need for a coherent and consistent long-term vision and strategy. Sectoral reform processes can take years, and require consistent structural action over time.”

— EuroHealthNet

Therefore, despite increased attention on healthcare expenditure at the EU level, it does not sit at the same level as economic and climate concerns in the fiscal or political hierarchy, and is vulnerable to being sidelined. This is in part due to healthcare being a national competence as well as to the lack of a unified and consistent EU-wide vision for the future of healthcare. In contrast, for digital transformation, where the EU has a clear vision, MS report on their progress towards the Digital Decade Policy Programme within the Semester. It is also hard to determine how much the Semester forces MS to undertake new health initiatives compared with MS forcing existing action into the Semester reporting.

Overall, the Semester process is useful for fiscal transparency, but it is unclear how much of its recommendations and reporting requirements drive new health or e-health initiatives.

Recovery and Resilience Facility

The Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), was introduced in 2021 to help EU countries address the economic and social impacts of the COVID-19 crisis. It is a one-off facility, offering €723 billion, comprising €385.8 billion in loans and €338 billion in grants, allocated to MS on a GDP and unemployment basis. To date €232 billion of these funds have been disbursed.

MS have each set out spending plans called Recovery and Resilience Plans, or RRPs, which are to be implemented by the end of 2026. These plans must further the green transition (spending at least 37% of funds in this area), and support the digital transition (spending at least 20% of funds in this area). They must also address their individual CSRs from the European Semester.

Of these plans, around €43 billion have been allocated to healthcare and digital health initiatives, representing around 6% of the funds. Of this, a substantial amount of spending has been allocated to digital health, around €12 billion according to a 2021 analysis.

Planned investments include improving national health data platforms and their use, including electronic patient record systems, data analytics, and telehealth services. However, given that EU healthcare expenditure totals around 10% of GDP and over 15% of government expenditure, it could be argued that health is underrepresented in the spending mix. Moreover, even where healthcare is represented, the funds allocated in RRPs vary hugely across EU countries, suggesting that it is not consistently prioritized by Member States (see Fig 2 and 3).

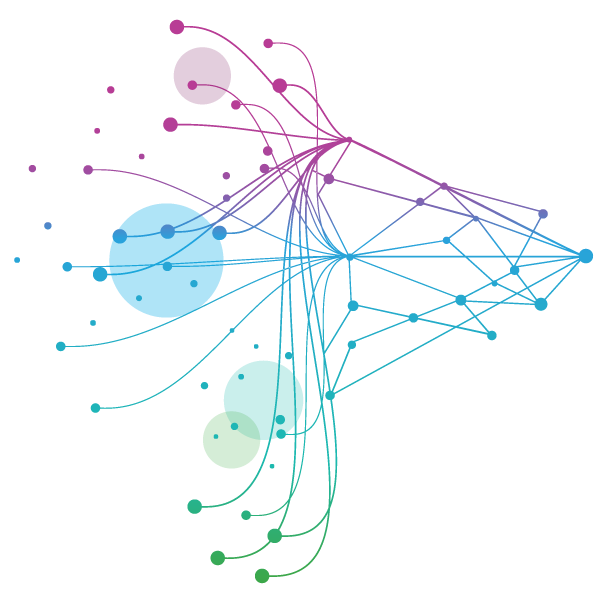

Figure 2. Percentage of Member States RRP’s designated as “Health and long-term care”.

Source: IQVIA EMEA Thought Leadership analysis of European Commission Data.

Notes: These should be seen as indicative figures only. The funds included are those designated as ‘Health and Long-term Care’ by the European Commission in accordance with its reporting requirements under Regulation (EU) 2021/2105, as well as data identified within Estonia and Belgium's RRP. The Commission’s classifications do not capture all health-related funding and may not be up to date with modified recovery and resilience plans.

Figure 3. Total amount of Member States’ RRP’s funding designated as “Health and long-term care”.

Source: IQVIA EMEA Thought Leadership analysis of European Commission Data.

Notes: These should be seen as indicative figures only. The funds included are those designated as “Health and Long-term Care” by the European Commission in accordance with its reporting requirements under Regulation (EU) 2021/2105, as well as data identified within Estonia and Belgium's RRP. The Commission’s classifications do not capture all health-related funding and may not be up to date with modified recovery and resilience plans.

Nevertheless, there are some trends in how MS have allocated their RRPs to health. For example, the less developed MS have generally allocated a larger portion to “Health and long-term care”, whilst unsurprisingly, the larger economies are spending more overall. It is notable that the richer, smaller states have barely allocated anything.

In terms of real impact, as per the Commission’s mid-term evaluation, MS reported an increase in capacity of 45m patients per year at healthcare facilities modernized through RRF investments.

Case study - France - Catching up on technical standards for digital health

France has dedicated €2bn of its RRP to a policy of “Catching up on technical standards for digital health”. In its RRP, France acknowledges a “chronic lack of investment in digital healthcare”, and that “the majority of data exchanges in the care pathway are still paper-based”. In light of this issue, which is described as “a major obstacle to the development of new digital tools”, the policy proposes to “develop nationwide exchanges of health data under secure conditions”. Its specific success indicator is to add 15 million documents to the ‘Shared Medical Record’ system (now part of “My health space”) by 2025. This doubtlessly anticipates future implementation of the European Health Data Space, the EU’s ambition to interlink health data across the region.

France’s digitalisation ambitions link directly to the policy guidance provided in European Semester documents. The 2021 ‘Staff Working Document SWD(2021) 12 final: Guidance to member states, recovery and resilience plan’ specifically suggests “Supporting the development, uptake and upgrade of Electronic Health Records…”. It also indicates the alignment of the policy with its 2020 Country Specific Recommendations, which recommend “further decisive efforts to digitalise health services”. This example suggests tha, the RRF has the potential to empower the European Semester to influence the digital health policies of MS.

In terms of digital health, MS seem to have seized the RRF as an opportunity to invest. According to the EU Commission’s 2021 thematic analysis of healthcare in RRPs, digital health measures appear in the RRPs of at least 18 countries. The thematic analysis of digital public services reported that countries had planned policy reforms in the area of healthcare data, to enable the interlinkage and re-use of health data and to fund preparations for the European Health Data Space. A mid-term evaluation and dedicated review analysed several cases of digitalization of healthcare, including projects to roll out telemedicine in Croatia and Denmark, and found them effective and coherent with CSRs.

Overall, the RRF is a powerful tool for developing healthcare data infrastructure. It provides a financial incentive for countries to follow recommendations made under the Semester process, which has resulted in many digital health projects receiving funding (perhaps due to the 20% digital ringfence). However, possibly as a result of the focus on digital and green initiatives, health spending overall appears to be underrepresented in the allocation of RRF funds in comparison to its typical proportion of government expenditure. Also, as the RRF is a one-off measure which will be completed in 2026, it is unclear whether digital health projects will continue to receive as much attention when the funding dries up.

Cohesion Policy Funds

The Cohesion Policy Funds, known as the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF), are aimed at reducing inequality across the bloc. They total ~€370bn and include:

- The European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), which distributes funds at the sub-national, regional level. Totaling €226.05 billion for 2021-2027 period

- The European Social Fund Plus (ESF+), focusses on employment, education & skills and social inclusion. It operates under “shared management” by the Commission and the MS. Totaling €99.26 billion for 2021-2027 period

- The Cohesion Fund (CF), which is specifically targeted at poorer Member States - Totaling €48.03 billion for 2021-2027 period

These funds are directed towards projects in a top down and bottom-up manner, but decisions are made at the bottom: MS or regional level. From the top, they are channeled towards EU policy priorities, including five overarching themes within which health is only a sub-priority. And from the bottom they are directed to country or regional priorities - including the Country Specific Recommendations coming out of the Semester process - with priority given to poorer regions. This duality is blurred in the ESF+, which operates under its own form “shared management”, with the Commission and MS jointly setting the overarching priorities.

Between 2014-2022, the ESIF has seen over €6bn of EU money directed to healthcare infrastructure, and over €700mn to digital health (individual projects are listed here). For the present period of 2021-2027, around €7bn is planned for healthcare access, although these funds are notorious for underspending their agreed allocation, with 40-60% of the total funds typically being unclaimed. This is due in part to the administrative difficulties in running the projects and applying for the funds, as well as receiving the public and private co-funding many of these projects require.

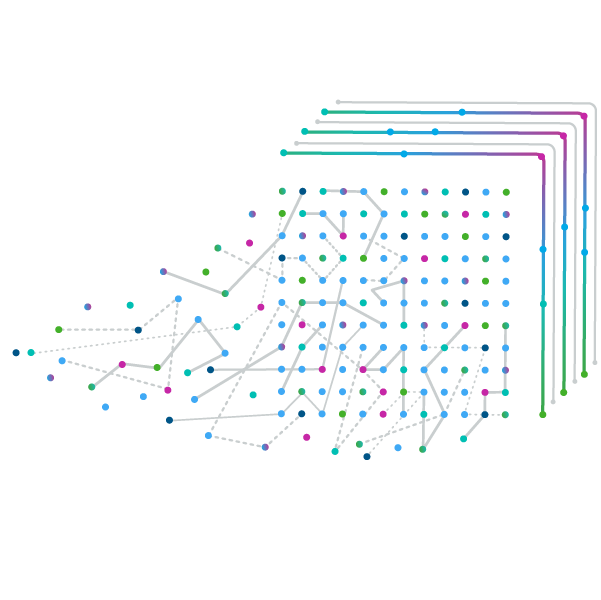

Figure 4. A sample of EU Cohesion Policy funding relating to health by Member State, 2014-2021 and 2021-2027

Source: IQVIA EMEA Thought Leadership analysis of European Commission data

Notes: These should be seen as indicative figures only. The funds included are only those within the Commission’s classifications which differ in what they capture across the two periods and do not capture all health-related funding from the Cohesion policy funds. The funds for the 2014-2021 period are disbursable until the end of 2023, and so are unrepresentative. For the 2021-2027 period, the funds are unlikely to be fully dispersed as they are “planned” maximums.

The use of these funds differs hugely across the MS but, as expected, the less developed MS receive the most funding. There are some less-developed MS, however, which have failed to draw down funds in these health areas.

As with the RRFs, these funds do not have an overarching policy for directing investments into healthcare infrastructure and digital health. This is to be expected given their broad focus and bottom-up nature, however it makes it harder to predict where the funds will be allocated in the future. It also makes it harder to neatly track health spending (See Fig 4).

To continue with France as an example of what these funds are spent on, the Corse region allocated €30.3 million, 29% of the regions ERDF funds for 2021-2027, for transformation of its healthcare infrastructure, including digitalisation of various services and telemedicine platforms to access them. This is to improve the differing levels of healthcare access across the mountainous island whilst enhancing the quality of care and working conditions of healthcare professionals.

Overall, the diversity and bottom-up nature of the Cohesion Policy Funds, combined with the lack of a common health priority, have left a mixed but positive picture on their utility in healthcare and e-health expenditure.

European Investment Bank

The EIB is the development bank of the EU, investing over a trillion dollars since its establishment in 1958 and approving €75bn in finances in 2022. Rather than being an EU institution, it is owned by the MS and is financially autonomous, raising money by issuing bonds on capital markets. It then provides loans, investments, guarantees and other support to public and private projects. Although semi-independent, it works closely with other EU institutions to channel investments towards EU policy priorities and foster European integration, particularly in climate and environmental sustainability.

The EIB serves as a quasi-fiscal mechanism for the EU to direct money without pulling from its limited core budget, which totals only €189.39 billion for 2024. And happily for MS, as an investment bank it makes them money - in 2022, €2.3bn. It also acts as a fund-manager for some MS to invest their RFF loans, which a handful are currently doing.

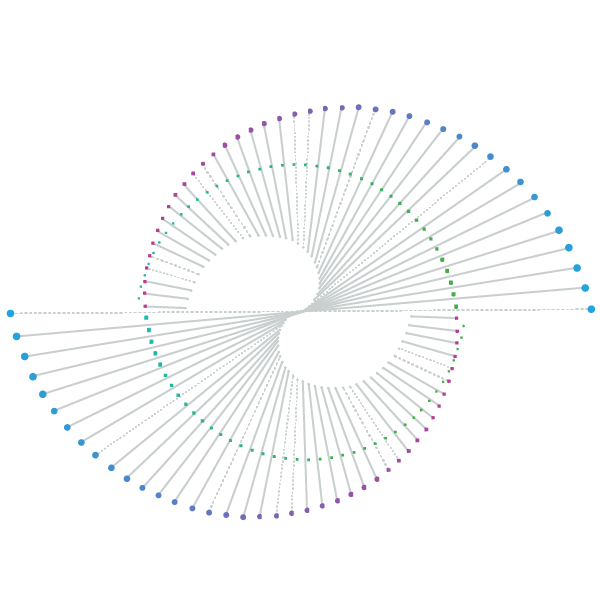

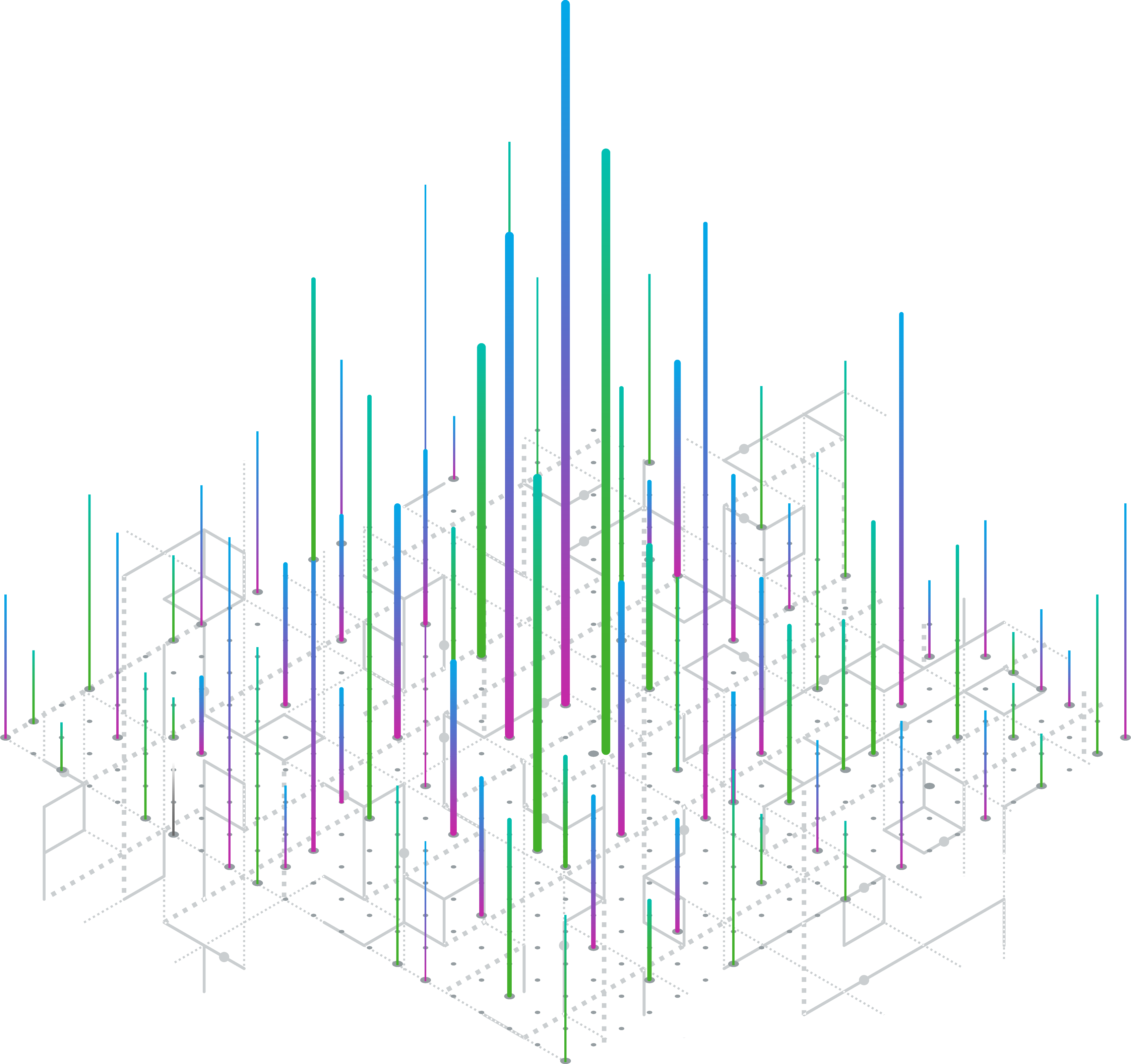

Figure 5. EIB financed projects in the health sector, 2010-2022

Source: IQVIA EMEA Thought Leadership analysis of EIB Data

Notes: Projects classified as in the Health sector by the EIB. It excludes other EIB support such as equity funds, and so should be considered indicative only.

The EIB has invested in a comprehensive range of health projects, although many of these are to fund healthcare facilities, particularly hospitals. Currently it funds close to 90 health projects. This portfolio grew in number and funding before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (See fig 5). As an example, in June 2020, the EIB funded BioNTech with a €100 million loan to help fund vaccine trials and manufacturing. This followed on from a €50 million loan in December 2019 to help the company work on cancer treatments. However, it is not clear whether this increase in health investment will be sustained.

In digital health, the Bank has also funded several projects, such as a €225m project in Ireland to introduce individual health identifier numbers for every patient in the country and establish an electronic health record system. In 2022, it invested > €5.1bn in health and life science projects, equaling around 8% of its loans it provided, a proportion unchanged for a decade. This proportion is similar to the 10% share of healthcare of EU GDP, but the use of EIB funds varies substantially across MS, with the larger and wealthier MS winning far more EIB investment (See fig 6).

Figure 6. Total EIB financing of health projects by Member State between 2010-2023

Source: IQVIA EMEA Thought Leadership analysis of EIB Data.

Notes: Projects classified as in the Health sector by the EIB. It excludes other EIB support such as equity funds, and so should be considered indicative only.

Overall, the EIB has provided a steady stream of financing for health and e-health that is driven less by policy priorities of the EU or MS and more by the market.

Overall findings

As with most EU tools, the fiscal mechanisms discussed in this blog have developed organically over the years, largely in separation. Some of these are top-down in nature and some are bottom-up. With no EU strategy in health to follow, these tools have varied in their application to health and digital health across MS. Nonetheless, they are directing enormous sums of healthcare funding and have seen a comparative neglect in interest from health stakeholders. Thankfully, amongst this complexity, the Semester process is proving an increasingly useful tool to align and a central focus of stakeholders seeking to influence these funds.

For the RRF, although all the MS’s plans have now been submitted, the difficult process of delivery is just beginning: MS have the task of translating a few lines of text into massive real world projects, and they (with the Commission) have limited administrative capacity for the complex disbursement of these funds. For projects in healthcare, this may prove particularly challenging as it is a field famously resistant to change. Another difficulty lies in the political approval of the disbursement of these funds. Due to the sums of money now involved, the politics permeating the Council could get in the way. Nevertheless, providing the EU fiscal powers through debt sharing at this scale sets a precedent, and one with large health implications. If this precedent survives past 2026, increased EU fiscal action in health should be met with greater engagement by stakeholders to ensure its effectiveness, particularly in meeting the digital future of healthcare.

The Cohesion Policy Funds and the EIB set priorities in both a top-down and bottom-up manner, with one focusing on equity, and the other on economic opportunity. This results in a seemingly unstructured, if efficient, distribution of funds, but makes it hard to track their impact on health and digital health beyond the size of the funds disbursed.

The use of these fiscal mechanisms varies across MS, reflecting the diverse economic and social landscapes across the European Union. In some countries, these funds have become integral to healthcare infrastructure, significantly improving access and the quality of healthcare services. Meanwhile, other countries have focused more on other sectors, including digital transformation initiatives, crucial for future economic growth and competitiveness. This variation, and the variation in use of the funds, is also a reflection of differing administrative and institutional capacities; MS with less developed administrative capacity struggle with absorption and utilisation, risking underuse or misallocation.

Recognizing these disparities between MS, the EU is striving for a more cohesive policy framework. Efforts are underway to simplify application and reporting processes to facilitate better access and use of these funds. Additionally, there is a shift towards outcome-based assessments, moving the focus from merely the size of the funds to their concrete impact on communities and sectors (here). However, fraud has recently, and inevitably, tarnished the RRF, making planned administrative simplification more complicated.

Looking to the future, a new Parliament and Commission will begin negotiations on the shape and scale of these fiscal mechanisms for the next seven-year financial period. The outcome of these negotiations will, paradoxically, depend less on their economic benefits to date and more on political will. Within these negotiations, health stakeholders should raise their voice in relevant public consultations that may be economic in nature but impact health in reality. More broadly, these tools help deliver EU priorities, but in health there is a lack of an EU vision for them to deliver. This leads to a disconnect of these tools with other EU policies in health, such as the aims of the EU’s pharmaceutical revision. The next political cycle offers an opportunity to create an overarching vision for EU action in health. This could anchor these fiscal funds and ensure the consistency and concentration of EU funding and policies.